By Brig Syed Karrar Shah, Retired

Geography and History

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) stretches across East Asia with an area of roughly 9.6 million square kilometres, making it one of the world’s largest countries. To its east lie the Pacific coasts and vital seas; to the north, the steppes of Mongolia and Siberia; to the west, the great plateaus and deserts leading toward Central Asia; and to the south, tropical and subtropical belts bordering Southeast Asia and the Himalayas. China’s major river systems—the Yangtze (Chang Jiang), Yellow River (Huang He), and Pearl (Zhujiang)—have nourished civilizations for millennia and shaped densely populated basins and fertile plains. Its diverse landscapes include the Tibetan Plateau (the “Roof of the World”), the Gobi Desert, the karst country of Guangxi, and coastal megacity belts from the Bohai Rim down to the Pearl River Delta.

Chinese history is among the world’s longest continuous narratives. Early Neolithic cultures along the Yellow River gave rise to Bronze Age states and, ultimately, the imperial cycles. The Qin unification (221 BCE) standardized weights, measures, and script; the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) consolidated a bureaucratic state and opened the Silk Road. Later dynasties—Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing—oversaw waves of innovation, population growth, and global exchange. The 19th and early 20th centuries brought foreign incursions, unequal treaties, and internal upheavals, culminating in the fall of the Qing (1911) and a long struggle between competing national forces. After World War II and the Chinese Civil War, the PRC was founded in 1949 on the mainland, while the Republic of China (ROC) government relocated to Taiwan.

China in the Era of the Holy Prophet (ﷺ)

By the 7th century CE—the era of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ)—China was already a renowned center of crafts, paper-making, ceramics, and learning, linked to the Islamic world via terrestrial and maritime Silk Roads. Muslim merchants and envoys reached Tang China; over centuries, flourishing Hui and other Muslim communities developed within China’s cultural mosaic.

A well-known saying often heard in sermons and writings is: “Seek knowledge even if you have to go as far as China.” Classical hadith scholars, however, assessed this wording as weak. The sound, widely accepted hadith is: “Seeking knowledge is obligatory upon every Muslim,” without specifying China. The spirit of the oft-quoted phrase captures Islam’s esteem for learning, and China symbolizes distance and excellence in knowledge in the Muslim imagination—but academically, we should distinguish between the popular saying and rigorously authenticated reports.

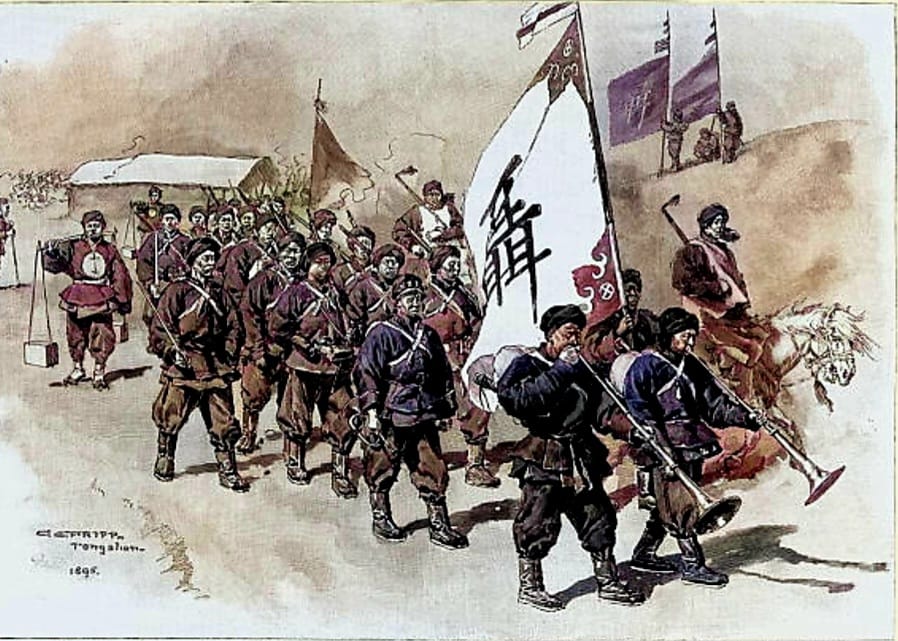

The Japanese Invasion, Chinese Resistance, and Japan’s Surrender

Modern China’s crucible came during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which merged into the broader World War II conflict in Asia. Japan’s invasion brought immense suffering: brutal occupation, siege warfare, forced labour, and atrocities like the Nanjing Massacre. Yet Chinese resistance endured—across Nationalist (Kuomintang) armies, local militias, and Communist-led guerrilla forces—through protracted campaigns from Shanghai and Wuhan to the series of battles at Changsha and in China’s vast interior. By 1945, Japan’s defeat became irreversible, leading to imperial capitulation.

Japan’s formal surrender was signed on September 2, 1945, aboard the USS Missouri, in the “Japanese Instrument of Surrender,” which ended hostilities in World War II. This document marked the legal conclusion of the war and the end of Japanese occupation across East Asia, including Chinese territories that had suffered under invasion. The courage and sacrifice of the Chinese population—soldiers and civilians—were essential to the Allied victory in Asia and remained honoured in national memory.

China’s Economy and the Share of Poor People When Japan Left

Measuring poverty in the immediate post-war years is challenging: reliable national household survey systems did not exist in 1945, and the nation shortly plunged into civil war (1945–1949). What we can say with confidence is that by the time the PRC was founded in 1949, China was overwhelmingly agrarian, its infrastructure devastated, and core social indicators were extremely low: life expectancy hovered around 35–40 years—a stark proxy for widespread deprivation, poor nutrition, and limited public health capacity. Literacy rates were likewise modest, and industry was concentrated in a few coastal cities.

Comparable, internationally consistent poverty estimates become available much later. Using the World Bank’s international extreme-poverty line (US$1.90/day, 2011 PPP), about 88% of China’s population lived in extreme poverty in 1981, the first year of comparable data. This figure underscores how deep poverty remained decades after the war and prior to full-scale reforms taking hold; it also provides a baseline for understanding the transformation that followed.

Today’s Chinese Economy and the Roots of Rapid Growth

In the late 1970s, China embarked on “reform and opening up” under Deng Xiaoping. Agricultural decollectivization (household responsibility system), the permitting of private and township-and-village enterprises, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in coastal areas, and an export-oriented industrial strategy began unleashing productivity gains. Over time, China integrated into global supply chains, attracted foreign investment, expanded infrastructure, and steadily upgraded from labor-intensive assembly to higher-value manufacturing and technology.

The results were historic: since 1981, China has lifted roughly 800–850 million people out of extreme poverty—an achievement without precedent in human history—and it has become the world’s second-largest economy by nominal GDP and the largest by purchasing power parity (PPP). Recent World Bank/IMF datasets show China as a global economic heavyweight, though growth has moderated compared to double-digit rates seen in the 2000s.

Key drivers of China’s rapid rise included:

1. Market-oriented reforms that incentivized entrepreneurship and productivity while retaining a strong state role in strategic sectors.

2. Export-led industrialization, leveraging a vast labour pool to become “the world’s factory.”

3. Massive infrastructure build-out—ports, highways, high-speed rail—lowering logistics costs, and knitting the national market together.

4. Human capital accumulation, expansion of basic education, and later, ambitious R&D investments.

5. Urbanization, moving hundreds of millions from farms to factories and services, increasing incomes and efficiency.

6. Global integration, including WTO accession in 2001, deepened trade and investment ties.

Although China’s growth is facing some challenges like demographics (a shrinking workforce), productivity slowdowns, real-estate imbalances, and geopolitical headwinds. Yet, it continues to push into advanced manufacturing (EVs, batteries, solar), digital platforms, and strategic technologies.

China–Pakistan Relations: An “All-Weather” Friendship

Pakistan and China describe their bond as an “All-Weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership.” The relationship rests on mutual trust, security cooperation, and economic connectivity. In 2015, both sides launched the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, aimed at upgrading Pakistan’s energy, transport, and industrial infrastructure from Kashgar in Xinjiang to Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea. Over the years, the two countries have cooperated on defence production (e.g., JF-17 Thunder), counterterrorism, and development finance. Official joint statements consistently reaffirm the closeness of the partnership and the goal of a “community of shared future.”

Recent engagements show the relationship’s continued relevance. On August 21, 2025, the foreign ministers of China and Pakistan met in Islamabad and agreed to launch new CPEC projects and deepen cooperation in science, technology, agriculture, and industry—while emphasizing the importance of security for Chinese personnel in Pakistan. This underscores both sides’ intention to adapt and advance the corridor in changing regional and economic conditions.

At the same time, the landscape of development finance is evolving. For example, reports note that the Asian Development Bank is stepping in to finance a key Karachi–Rohri rail upgrade, amid delays in some China-linked funding, with coordination among partners to keep strategic connectivity on track. This reflects a pragmatic blend of financing sources serving Pakistan’s infrastructure needs, not a departure from the broader China–Pakistan partnership.

Tribute to the Chinese Nation and Its Heroes

The War of Resistance against Japan exacted a tremendous cost on China. Entire cities were bombed, industrial zones dismantled, and millions displaced. Yet the Chinese people persevered—soldiers on the front lines, guerrilla fighters behind enemy lines, and civilians who sustained production, carried intelligence, and endured occupation. Their courage contributed decisively to Japan’s ultimate surrender and the Allied victory in Asia. Today, memorial museums, literature, and national commemorations keep alive the memory of those who fought and fell. The lessons—fortitude under adversity, unity across factions in the face of invasion, and the resolve to rebuild—continue to inform China’s national ethos.

Conclusion

China’s story is one of vast geography, deep history, and extraordinary transformation. From the river cradles of ancient dynasties to the globalized metropolises of the 21st century, it has navigated cycles of unification and disunity, encounters with the outside world, and trials of invasion and civil strife. The much-loved saying about “seeking knowledge even as far as China”—though not authenticated in hadith science—nevertheless captures a timeless truth: the pursuit of knowledge is central to civilizational vitality. In China’s case, openness to learning, experimentation, and adaptation—especially since the late 1970s—has powered one of the greatest economic ascents in history, taking hundreds of millions out of poverty and reshaping the global economy.

For Pakistan, China remains an ever-tested friend: a partner in connectivity, energy, and industry, and a strategic counterpart across diplomacy and defence. CPEC and related initiatives continue to evolve, with both countries reaffirming their commitment to cooperation while incorporating new partners and financing models where helpful. The trajectory suggests that the China–Pakistan bond will endure—tested by realities on the ground but sustained by shared interests and decades of trust. As the world enters an era of technological competition, climate transition, and shifting trade patterns, China’s geography, history, and accumulated capabilities ensure that it will remain a central actor—one whose past struggles and present ambitions will continue to shape Asia and the world.