By Brig Syed Karrar Shah retired.

Geographical location and importance

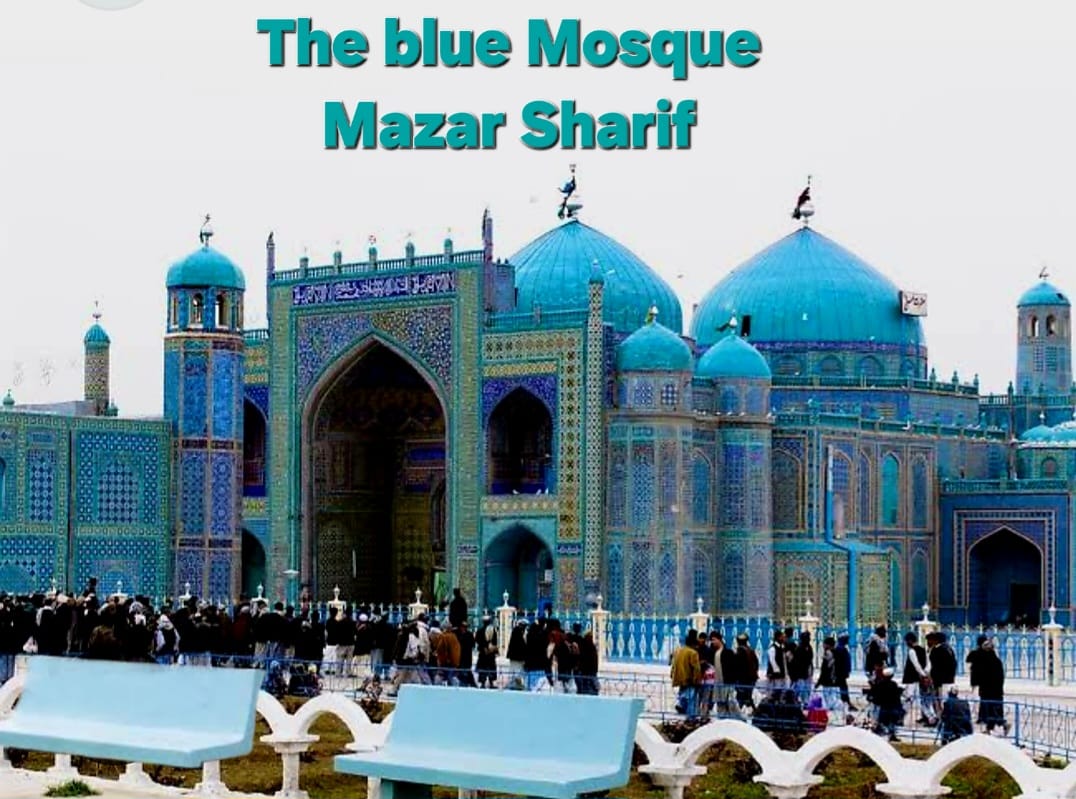

Afghanistan sits at the heart of Asia, landlocked yet strategically positioned where South, Central, and West Asia meet. To the east and south lies Pakistan; to the west, Iran; to the north, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan; and to the far northeast a sliver of high valleys touches China along the Wakhan Corridor. This crossroads geography has shaped Afghanistan’s fortunes for millennia. Mountain chains—most notably the Hindu Kush—slice the country into distinct basins and highlands, complicating travel and state control but protecting local autonomy. North–south passes (like Salang) and east–west river valleys (such as the Hari Rud and Helmand) funnel trade, armies, and ideas.

Afghanistan’s location makes it a potential bridge for regional energy, transport, and digital corridors connecting Central Asian resources and markets to ports in Pakistan and Iran. It fronts the historical Silk Route and modern initiatives like the Central Asia–South Asia power lines and fiber links. Yet the same location exposes it to geostrategic competition, sanctions pressures, and the leverage of neighbors over transit and trade. The state’s development prospects, therefore, depend as much on regional politics and border management as on domestic policy.

History of the Afghan nation and its long struggle against invaders

Afghanistan’s recorded history is a succession of empires, confederations, and autonomous polities. Achaemenid, Macedonian, Kushan, Sasanian, and Islamic caliphate rule left layers of culture; the Ghaznavids and Ghorids projected power outward; and the Timurids made Herat a center of Persianate art. In 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani forged a modern Afghan state, drawing on Pashtun tribal confederations but integrating Tajik, Hazara, Uzbek, and other communities into a loose imperial framework.

Foreign incursions—from the three Anglo-Afghan wars (19th–early 20th centuries) to the Soviet invasion (1979–89) and the U.S.-led intervention (2001–2021)—met fierce resistance. The country’s rugged terrain, social networks, and the moral vocabulary of faith and honor repeatedly undermined outside military campaigns. Afghans often combined local defense with shifting alliances, making occupation costly and state-building by foreigners fragile. The withdrawal of Soviet forces in 1989 culminated in state collapse and civil war; the Taliban first rose in the 1990s promising order, fell in 2001, then returned to power in August 2021 after a twenty-year insurgency and the collapse of the internationally backed republic.

Across these cycles, a persistent theme is Afghan resilience against external control—sometimes unifying disparate groups, sometimes fracturing along ethnolinguistic and factional lines. This history instilled a suspicion of foreign designs but also left a legacy of weak central institutions and recurring conflict that continues to shape politics and development.

Present political system: structure, Islamic Sharia foundations, strengths and constraints

Since August 2021, Afghanistan has been governed by the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA). Authority is concentrated in the Supreme Leader (Amir al-Mu’minin), Hibatullah Akhundzada, based largely in Kandahar. He rules through decrees grounded in the leadership’s interpretation of An acting prime minister and cabinet in Kabul manage day-to-day administration and issue decisions subject to the Supreme Leader’s approval. The previous republican constitution and parliament were dissolved; decision-making is centralized, and formal checks and balances are limited. Analyses describe the system as centralized with rule by decree including the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice and provincial ulema councils.

Strengths often cited by the authorities and some observers

Improved internal security and anti-corruption messaging. The Emirate emphasizes that the end of large-scale insurgency and the consolidation of control have reduced roadside violence in many areas compared to peak war years. Centralized appointments and revenue collection are presented as steps against graft. Independent reporting also notes tighter revenue administration—even while aid has fallen sharply. World Bank analysis finds domestic revenue mobilization remained relatively strong through 2024, though far from sufficient to replace lost foreign assistance.

Macroeconomic stabilization of the currency. Despite sanctions and frozen reserves, the afghani appreciated through much of 2023–24 before softening late in 2024; deflationary pressures were evident in 2024 as well. This currency stability—managed through cash auctions, strict capital controls, and external inflows—helped temper price spikes, though it also hurt export competitiveness.

Opium ban enforcement—contested outcomes. The leadership highlights a nationwide ban on narcotics production as a moral and governance achievement. UNODC reported an approximately 95% collapse in opium cultivation in 2023 following the ban. However, newer imagery-based assessments suggested a rebound in 2024; the picture is still debated. The contrast underscores implementation challenges and the need to replace lost farm incomes.

Constraints and criticisms by the Western media

Human rights and inclusion concerns persist. Restrictions on girls’ secondary and higher education and on women’s employment remain the principal barrier to international recognition and engagement—cited across multilateral and rights reports.

Economic base: natural resources, agriculture, trade patterns, and recent achievements

Natural resources

Afghanistan is widely believed to hold significant deposits of copper (Mes Aynak), iron ore (Hajigak), gold, coal, gemstones (lapis, emeralds), and potential lithium and rare earths, though most deposits remain undeveloped due to security, infrastructure, water, and governance hurdles. USGS and allied technical work detail the scale and geology of key sites, including Mes Aynak’s large copper resource and the world-class potential of Hajigak iron ore. Environmental baselining has continued in recent years to prepare for any future extraction.

Hydrocarbon potential exists in the Amu Darya and Afghan-Tajik basins. Small onshore projects and refined-product imports dominate today, but contracts with regional companies have been pursued since 2023. Much of the sector’s viability depends on transit options, political risk, and access to finance.

Agriculture

Agriculture remains the largest employer. Wheat is the staple; orchards (pomegranates, grapes, apricots), nuts (almonds, pistachios), and niche crops like saffron provide cash income. After drought years and market shocks, wheat output reportedly improved in 2024, yet the country still imports substantial volumes to close the consumption gap. FAO emphasizes that targeted seed, irrigation, and extension support could move the sector closer to self-sufficiency and better nutrition outcomes.

Exports and imports

Afghanistan’s export basket includes dried and fresh fruits, nuts (notably pine nuts to China), carpets, and—until taxes and Pakistani demand shifted—coal exports to Pakistan. According to the World Bank’s April 2025 update, overall exports fell in 2024 while imports surged, widening the annual trade deficit to about $9.4 billion. Coal export revenues dropped sharply (down ~40% in 2024, after a ~65% fall in 2023), whereas food exports showed some resilience. The strong afghani and trade frictions reduced competitiveness. On the import side, fuel, wheat/flour, machinery, textiles, and basic goods dominate, with Russia and Kazakhstan supplying grain and flour in recent years.

Fiscal and monetary picture

Domestic revenue effort—customs, non-tax fees, and state-owned entities—has been relatively robust, but the collapse of on-budget aid has left large gaps for public investment and service delivery. Monetary transmission is constrained by a cash economy, limited banking intermediation, and compliance challenges. The World Bank estimates real GDP growth of about 2.5% in 2024, driven mostly by agriculture and real estate activity, but warns that poverty and food insecurity remain widespread and the external position fragile.

Achievements since 2021 often cited domestically (and how they look in practice)

1. Security consolidation: The end of front-line war has reduced mass-casualty violence in many corridors, allowing road freight and inter-provincial travel to normalize compared to conflict peaks. This is widely acknowledged, though threats from ISIS-K and localized violence persist.

2. Revenue and administration: Centralized customs management and routine fee collection increased state takings relative to 2021–22 lows, even if still far below the needs once funded by international grants. The “clean government” narrative is powerful domestically, though independent verification is uneven and service-delivery investment remains limited.

3. Currency stability: Despite isolation and frozen reserves, the afghani’s relative strength through much of 2024 kept some import prices in check, aiding urban consumers—at the expense of exporters. Late-2024 depreciation highlighted how dependent stability is on external cash inflows and controls.

4. Narcotics ban enforcement: The 2023 collapse in opium cultivation noted by UNODC was extraordinary. But sustaining it without alternative livelihoods is hard; competing analyses showed signs of resurgence in 2024. Policymakers face a dilemma: uphold the ban for moral and health reasons while preventing rural impoverishment.

Expected future growth: opportunities and risks

Opportunities.

Transit and regional connectivity. Afghanistan can monetize geography if it becomes a reliable corridor: electricity transit (CASA-1000-style lines), fiber backbones, and road/rail links from Central Asia to Pakistani or Iranian ports. Stability along the Ring Road, predictable border procedures, and dispute resolution would unlock trade rents and lower costs for Afghan producers.

Agro-value chains. Cold storage, grading/packaging, SPS standards, and cross-border logistics for fruit, nuts, and saffron can raise rural incomes. Substituting wheat flour imports with domestic milling of imported grain (as officials have discussed with Russia) could capture more value onshore.

Selective mining. Starting with comparatively “shovel-ready” deposits (dimension stone, cement, some metals) under credible environmental and community frameworks could build capacity ahead of mega-projects like Mes Aynak or Hajigak. USGS baselines at Aynak and decades of iron-ore studies at Hajigak provide technical starting points, but governance and water constraints are decisive.

Diaspora and regional capital. Small and medium investments from Afghan traders and regional firms can scale services (logistics, wholesale, construction materials) if currency stability, property rights, and dispute resolution improve.

Risks.

External financing and aid retreat. With on-budget aid collapsed and access to international credit constrained, public investment in health, education, water, and roads faces chronic underfunding. This suppresses human capital and long-term growth.

Trade vulnerability. The trade deficit widened markedly in 2024 as the strong afghani and frictions with neighbors hurt exports. Without diversification and logistics cooperation, Afghanistan will remain dependent on imported essentials and vulnerable to regional shocks.

Human capital restrictions. Continued limits on girls’ education and women’s work depress labor productivity, cut household incomes, and deter investors—an economic as well as moral cost documented across development literature and rights reporting.

Illicit economy dynamics. Sustaining the opium ban without viable alternatives risks rural hardship and potential instability; backsliding would re-expose Afghanistan to criminal capture and international sanctions.

Conclusion

Afghanistan’s destiny has always been entangled with geography: a mountainous crossroads whose valleys connect civilizations. That geography is at once an asset and a vulnerability. Over centuries, Afghans have resisted imperial adventurism and shouldered the costs of great-power competition; the last half-century of war and state collapse have left deep institutional and human scars.

Today’s Islamic Emirate governs through a centralized, Sharia-based framework anchored in the Supreme Leader’s decrees, with a Kabul cabinet executing policy. The system’s asserted strengths—restored security in many areas, tighter revenue collection, currency stabilization, and narcotics prohibition—have produced visible changes on the ground. Yet the model faces binding constraints: limited international recognition, restricted participation of women in public life, a thin fiscal base, and structural trade imbalances. Independent data show the economy grew modestly in 2024 (about 2.5%), supported by agriculture, but poverty and food insecurity remain widespread. The trade deficit widened sharply as exports fell and imports surged, with a strong afghani undermining competitiveness.

The pathway to future growth lies in practical steps more than grand designs: predictable border regimes; cooperation with neighbors on transit, power, and standards; rehabilitating irrigation and rural roads; expanding cold chains and milling capacity; and piloting transparent, environmentally sound mining that shares rents with communities. Above all, human capital—education for girls and boys, technical training for young workers—will determine whether Afghanistan can escape low-productivity traps. Without a broader social compact that mobilizes the talents of all Afghans, investment will hesitate, and opportunities will pass to better-prepared neighbours.

Afghanistan’s story has never been linear. But the country’s innate assets—its location, its resource endowment, and the resilience and entrepreneurship of its people—remain real. If governance can evolve toward inclusion and predictability, and if regional pragmatism continues to open trade doors, Afghanistan can gradually move from survival to sustained, dignified growth. That shift will require balancing moral claims with livelihood realities, marrying central authority to local consent, and pursuing economic policies that privilege agriculture and small enterprise while laying the groundwork for future industry. In that balanced approach lies the best chance to convert a history of endurance into a future of shared prosperity.