MUKHTAR AHMED BUTT

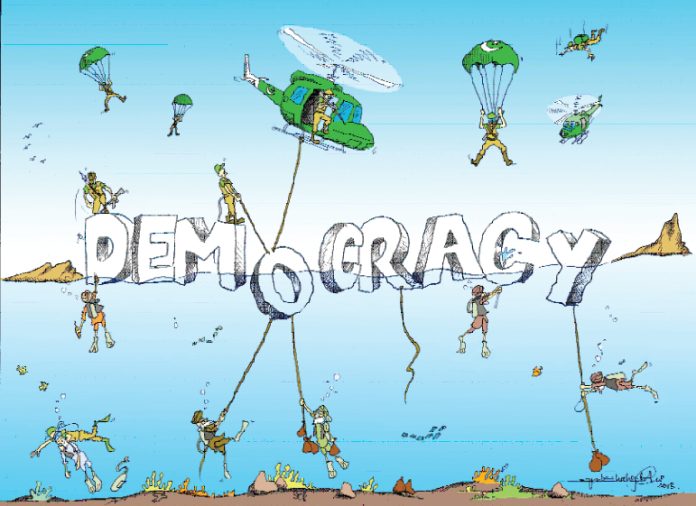

The passage of the 27th Constitutional Amendment marks a new and significant turn in Pakistan’s political history. Without the imposition of martial law or overt military intervention, the establishment has successfully redefined the constitutional balance of power. In essence, the amendment formalizes what has long been an informal reality the dominant role of the establishment in determining the trajectory of the state. While the move is presented as a step toward political stability and governance efficiency, its implications extend far deeper. It symbolizes the gradual institutionalization of hybrid governance a system in which elected representatives function within parameters set by unelected power centers. This development has far-reaching consequences for Pakistan’s domestic politics, governance structure, and international image. But, this must be stated categorically it was not the requirement of establishment but of our leaders and rulers who always needed crutches of the establishment. Pakistan’s defense minister, Khawaja Asif, has publicly praised the country’s “hybrid system” which he describes as a model where civilian and military leadership share power by consensus. Since independence, Pakistan has struggled to establish a consistent equilibrium between civilian authority and military influence. Frequent military interventions, from Ayub Khan to Musharraf, interrupted democratic continuity and created a deep structural dependency of civilian institutions on the establishment. Over the years, even during democratic periods, the political class has often sought the establishment’s mediation in political crises including superior courts. Instead of evolving as autonomous entities, most political parties have leaned on the establishment to resolve intra-party disputes, form coalitions, or secure electoral advantages. The 27th Amendment, therefore, emerges from this historical backdrop as an abrupt deviation but as a logical culmination of decades of civil-military imbalance. What distinguishes it from previous interventions, however, is its constitutional legitimacy. It places the establishment’s supervisory role within the legal framework, avoiding the stigma of martial law while maintaining strategic control.

Political scientists describe Pakistan’s system as a “hybrid regime” a form of governance that combines elements of electoral democracy with authoritarian control. The 27th Amendment gives this hybrid model a more structured form. Parliament remains intact, elections are held, and parties continue to function, yet the substantive power in areas of security, foreign policy, and key administrative decisions resideselsewhere. This arrangement produces two key outcomes:

Formal control without Martial Law. By embedding control within the constitution, the establishment achieved what previous martial laws could not control without coercion. The democratic façade is preserved, allowing Pakistan to avoid international censure and domestic unrest that usually accompany coups. This is an elegant form of constitutional engineering: ensuring power centralization without overt disruption and weakening of Civilian Institutions.

On the flip side, the amendment further erodes the autonomy of civilian institutions. Parliament’s role risks being reduced to a ceremonial forum that debates but does not decide. The legislative focus shifts toward personal privileges, development funds, and symbolic representation rather than meaningful policymaking. Such an arrangement breeds political apathy, weakens policy innovation, and perpetuates elite-driven politics where individuals seek alignment with power centers rather than accountability to voters.

Proponents of the amendment argue that Pakistan’s chronic political instability, corruption, and policy inconsistency justify a supervisory role for the establishment. They claim that centralization under disciplined, non-political leadership ensures national security and continuity of governance. In their view, elected governments have repeatedly failed to deliver, and thus a stronger establishment presence guarantees order and functionality. However, such reasoning conflates stability with democracy. True stability cannot emerge from control; it arises from legitimacy, inclusion, and institutional trust. When elected governments operate under invisible constraints, accountability blurs. No single institution can be held fully responsible for success or failure, as decisions are diffused through layers of influence. This lack of clarity fosters policy paralysis, where bureaucrats and ministers hesitate to take bold initiatives without seeking approval from non-elected quarters. Over time, it also discourages talented professionals from entering politics, seeing it as an arena stripped of real authority.

Perhaps the most profound internal effect of the amendment will be on Pakistan’s political parties gradually they shall become redundant, that is their own choosing. Over the years, most major political parties thePML-N, PPP, and PTI among them have evolved as personality-centric entities, reliant on patronage rather than ideology. The amendment’s reinforcement of establishment oversight deepens this dependency, leaving little incentive for parties to reform internally or build grassroots strength. Ultimately, the political system risks degenerating into guided democracy elections are held, governments change, but real power remains constant. Such systems, while stable in appearance, are fragile in substance, as they depend on informal understandings. Western democracies particularly the United States, the European Union, and Commonwealth partners are likely to interpret this move as a constitutional entrenchment of military influence. This perception can affect Pakistan’s diplomatic credibility and economic engagements. Institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, already pressing for governance reforms, may view Pakistan as moving away from transparency and civilian accountability.

Regional powers like China and Russia may interpret this transformation more positively. Their strategic philosophies prioritize stability over liberal democracy. A Pakistan governed under coherent central authority aligns well with their economic and security interests especially within the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) framework. For Beijing, a stable Pakistan ensures continuity of investment and a secure western corridor to the Arabian Sea. Thus, the amendment may further cement Pakistan’s strategic tilt toward China, even as it distances itself from Western democratic norms. In much of the Muslim world, where “guided democracy” is common, Pakistan’s move may not appear controversial. Countries such as Egypt, the UAE, and even Turkey operate under systems where the military or deep state retains a decisive say in governance. To these nations, Pakistan’s amendment may represent a pragmatic adaptation to its political culture rather than regression. The key question remains: can such a system sustain itself? History suggests that hybrid regimes enjoy temporary stability but struggle in the long run. Without genuine parliamentary oversight, a free media, and judicial independence, public alienation deepens. The 27th Amendment represents a quiet constitutional coup not in the sense of overthrowing democracy, but in redefining its boundaries that suits most of our leaders.The true measure of national strength lies not in who controls power, but in how power is distributed, contested, and accountable. Unless Pakistan’s political leadership rises above personal gain and embraces institutional reform, the Parliament will remain a symbolic body.