Syeda Farida Shah

On the evening of October 18, 2007, the city of Karachi stood electrified with hope and emotion. After eight long years of exile, Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan’s twice-elected Prime Minister, was returning home. The streets from Jinnah International Airport to Mazar-e-Quaid were flooded with jubilant supporters, men, women, and children waving flags of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), dancing, chanting, and showering rose petals. It was not merely a political welcome; it was a homecoming of a leader who embodied Sindh’s pride and Pakistan’s democratic aspirations.

As the truck carrying Benazir inched forward near Karsaz, surrounded by a sea of people, the night air thickened with the sounds of drums, slogans, and celebration. But beneath that charged energy lurked a sinister design. At around 12:10 a.m, the unthinkable happened. Two massive explosions ripped through the crowd, one after another, sending shockwaves across the city and the nation. The joyous chants turned into screams. Flames rose against the night sky. Bodies lay scattered across the road, mixed with torn flags and banners.

In the aftermath, more than 130 people were killed, and over 400 injured, mostly party workers who had formed human shields around their leader. Benazir survived, protected by the fortified vehicle, but the assassination attempt sent a chilling message that she was being hunted.

Benazir had received numerous warnings prior to her return. Intelligence sources, both local and international, had cautioned about potential attacks from extremist elements, particularly those angered by her outspoken stance against militancy and her alliance with Western powers. Yet, she insisted on returning, declaring that:

“the people’s love is my strength, and their prayers my protection.”

Behind the scenes, some of her closest aides recall that security arrangements were minimal and chaotic, despite repeated requests for armored escort and signal jammers. The long route from the airport to the city center, spanning nearly 18 kilometers was itself a risk, but Benazir refused to travel covertly. She wanted to be seen, to connect with the people who had waited years for her return.

Investigations that followed only deepened the mystery. Competing narratives emerged, some pointed fingers at militant groups, others whispered about the establishment uncomfortable with her anticipated political resurgence. Evidence, including forensic material, was never fully preserved. The Karsaz incident later foreshadowed her assassination in Rawalpindi just two months later, on December 27, 2007.

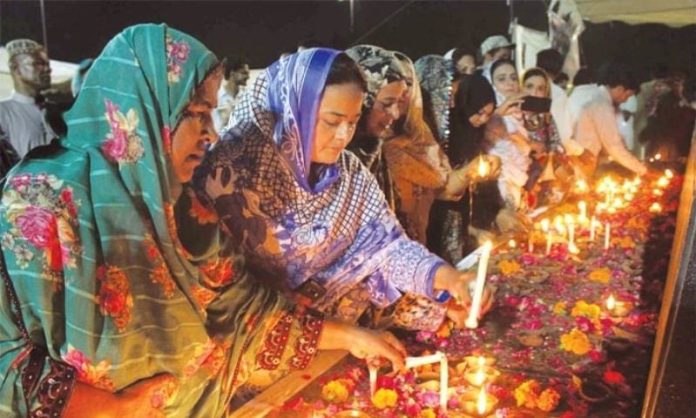

Sindh mourned, as no province ever had. For many, the Karsaz attack was not just an attempt on a leader, it was an assault on Sindhi identity, on democracy, and on the dream of a plural Pakistan. The spot near Karsaz became a site of pilgrimage, where flowers, candles, and tears were offered for those who fell protecting their leader.

Years later, the echoes of that night still linger in Karachi’s memory, of hope turned into horror, of devotion into sacrifice. The Karsaz tragedy stands as a symbol of resilience and a haunting reminder of the perils faced by those who challenged, and wanted change in Pakistan’s political landscape.